Information in this blog comes from my PhD thesis, “Managing Convicts, Understanding Criminals; Medicine and the development of English Convict Prisons, c.1837-1886” University of Leeds, 2017.

Date unknown. Photograph by Maull and Polyblank. Wellcome Library, London no.12300i.

William Baly (1813–61) was significant both for being an early Prison Medical Officer at Millbank Penitentiary and through his subsequent influence in the fashioning of the role of Prison Medical Officers at all prison institutions. Not only was he tasked with tackling disease at Millbank, he extended the scope of his role by reporting on cholera in Britain. Baly was the only famous (in some circles) Prison Medical Officer to appear in my thesis. He was involved in Millbank’s medical provisions through his role as a visiting doctor then as superintending medical officer from 1839 to 1859, before acting as Queen Victoria’s Physician Extraordinaire for the last two years of his life. Baly specialised in physiology and gastric disease, becoming a renowned expert in dysentery and cholera as a direct result of his work in Millbank and association with the Royal College of Physicians (RCP).

Baly was brought up in Norfolk where he attended the local Grammar school and was apprenticed to a local General Practitioner. In 1831, he began his medical studies at University College London (UCL), and in 1832 he began his pupillage at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. In 1834 he passed the examinations of the RCS and Apothecaries’ Hall. He spent two years abroad studying in Paris, Heidelberg, and Berlin. He graduated MD in Berlin in 1836. When he returned to England, he began general practice in London. He was also for a short time medical officer to the St Pancras Workhouse. In 1841 he became Millbank’s permanent medical superintendent following a dysentery outbreak. He had rooms on site, but his home was in Regents Park.

Between 1837 and 1842 Baly translated the eminent German physiologist Johannes Müller’s Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen (titled Elements of Physiology by Baly). Baly’s work was not only a translation but also a commentary on the text. He independently tested the contents, added new knowledge, and commissioned woodcuts. This book was very well received and was widely referenced. His independent work included “On Mortality in Prisons”, in Medico-Chirurgical Transactions (1845), and he presented on dysentery at the RCP’s Goulstonian Lectures (1847). In 1846 he became a Fellow of the RCP and in 1847 a Fellow of the Royal Society. Baly acted as censor of the RCP (1858–59) and sat as a crown representative on the General Medical Council. He lectured in forensic medicine at St Bartholomew’s Hospital from 1841, then in 1854 he became assistant physician there, and in 1855 began lecturing on medical courses at postgraduate level.

Given that Baly had an extensive research and teaching career, and could have expected to open a private practice or take on a hospital role like most of his contemporaries, why did Baly choose to work in a convict prison? The turning point of Baly’s career was the recommendation to go to Millbank and observe and report on epidemic dysentery by his teacher and colleague, Peter Latham. Baly was an inquisitive researcher and observer, so, despite having no particular expertise or interest in sanitation or dysentery at this time, he went to Millbank. In 1840 Baly was appointed to visit and report on health at Millbank prison following a series of epidemics. He was appointed by the prison inspectors and Secretary of State to work alongside the resident surgeon for twelve months to provide “vigilant supervision of the condition of prisoners in respect to health.” Baly began his attendance on 12 February 1840 and “devoted himself […] to the investigation of every point connected with the health and medical statistics of the Institution”.[1]

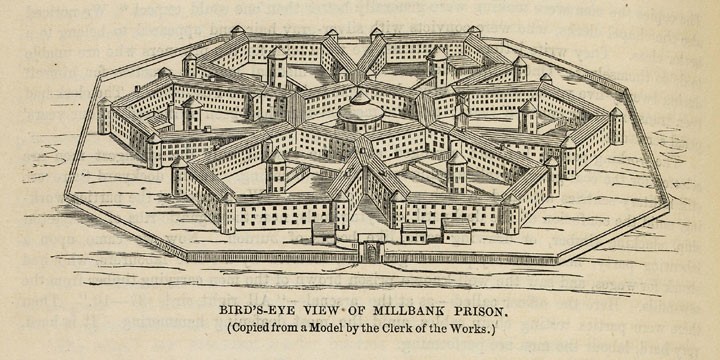

Henry Mayhew and John Binny (1862) The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life (The Great World of London). (London: Griffin, Bohn, and Company).: 232.

Baly’s obituary claimed that much of what he did at Millbank he did in order to earn a living. (Which is plausible, as he often was obliged to write to his father to request money, particularly to pay for subscriptions to journals or societies or for rent. Baly worked hard to stay abreast of medical training but also to maintain a good appearance personally and in his address.) But his personality meant he did everything with “scrupulous care” and with the intention of “honestly displaying the power with which he was prepared to enter on the contest of his life.” The obituary went on to say that the post at Millbank was advantageous to him for a number of reasons: a means of living when his private practice was short of patients, a large number of sick to care for, diseases of particular interest to contend with, and finally his coming into contact with government officers who trusted and appreciated him. Baly could not have known that the role would give him contacts in government making him “a principal medical adviser of government on questions of hygiene in prisons.”[2] But the previous three reasons, combined with the influence of his mentor Peter Latham, might have been enough to persuade Baly that Millbank is where he wanted to use his medical training.

Whilst at Millbank Baly became something of a ‘prototype’ for subsequent PMOs. This was not because he was in the first convict prison. Even if that had been the case, he was not Millbank’s first PMO. The superintendent medical officer at Millbank was the “de facto senior prison officer” because of William Baly. By 1842, when Baly was establishing himself, Millbank was no longer the “national penitentiary” having been replaced by the “model prison” at Pentonville. Other government-run prisons, such as Wakefield, Woking and Parkhurst, were also operational. Nevertheless, thanks to Baly, Millbank, rather than one of the new prisons came to be seen as the pinnacle of a PMO’s career, usually leading to a position as a prison inspector, government advisor, or in a few cases like Baly a royal physician. Baly made Millbank so important (despite its constant failures) by laying the ground work there of what a prison medical officer could do.

Baly died on 28 January 1861, when the train he was on from Waterloo to Portsmouth derailed on a bridge. Baly died in the crash and several other people were injured. His death was widely reported in national and local newspapers and in most medical publications. The Medical Times and Gazette wrote of Baly that “the real business of his life was practical medicine.”[3] This was something the journals considered praiseworthy, seeing Baly as an example of what a physician (not just a PMO) could be. The slightly gushing obituary pointed out that “he started in the crowd with neither wealth nor costly education…no brilliant genius, no lucky gift of cleverness” but had “efficiency of intellectual and moral excellence” for success to “literally go from the Prison to the Palace.”[4] The prison was not described, but the tone invited the reader to consider the class and number of people Baly dealt with, and therefore how strong his character must have been. His contemporaries and obituary writers saw him as a medical man rather than a PMO. There is an implicit assumption that the characterisation of Baly as a medical man rather than a prison medical man prioritising being a doctor over being a civil servant. Baly’s obituaries focused on his medical work, either minimising his prison work or, I believe suggesting his role in the prison was just another medical role. His lack of inclusion in nineteenth-century medical history is perhaps a reflection of later values placed on medical men inside state institutions which in Baly’s case, favour emphasis on government and royal connections. In part the lack of existing narratives about prestigious prison medical men goes some way to explain why PMOs have been left out of medical histories.

[1] Inspectors of Prisons of Great Britain I. Home District, Fifth Report, 1840: 199; Report of Committee of General Penitentiary at Millbank, 1840.

[2] “The Late Dr Baly” British Medical Journal. 1861 (9 February).

[3] “The Late Dr Baly” British Medical Journal. 1861 (9 February).

[4] “The Late Dr Baly” British Medical Journal. 1861 (9 February).

Leave a comment