At the BSHS postgrad conference this year I took the opportunity to present some research that I did last summer but hadn’t taken any further. It was interesting, I felt, but had no real argument at the time and thus was not publishable. The talk I gave at the conference still had no major argument other than work needs to be done on the subject which I hope to return to at some point. I felt it was something that people would be interested in.

The focus of my talk was Thomas Scattergood, who ended up being the Dean of the Medical School in Leeds. He was a physician and lecturer in chemistry and toxicology in Leeds and has been heralded as one of the first doctors of forensic medicine. I’m not convinced by that claim but he was certainly one of the most important men in the field in the nineteenth century, and probably the most important forensic expert outside of London. His notebooks cover a whole range of things. Many of which relate to poisonings and murder or attempted murder in the north of England. Forensic medicine became a recognised discipline in the nineteenth century growing alongside the medical and legal professions, very few medical men taught or studied forensic medicine at the start of the nineteenth century but by the end it was an integral part of medical education.

The focus of my talk was Thomas Scattergood, who ended up being the Dean of the Medical School in Leeds. He was a physician and lecturer in chemistry and toxicology in Leeds and has been heralded as one of the first doctors of forensic medicine. I’m not convinced by that claim but he was certainly one of the most important men in the field in the nineteenth century, and probably the most important forensic expert outside of London. His notebooks cover a whole range of things. Many of which relate to poisonings and murder or attempted murder in the north of England. Forensic medicine became a recognised discipline in the nineteenth century growing alongside the medical and legal professions, very few medical men taught or studied forensic medicine at the start of the nineteenth century but by the end it was an integral part of medical education.

Because conference presentations are limited to 20 minutes I couldn’t cover the full life and works of Scattergood, so took advantage of the fact it was a friendly audience to go to town on the powerpoint. With visuals in mind Scattergood’s work on arsenic poisonings and blood splatters were central to my talk. I never write out my talks so I’m just going to cover a few points here with the intention of writing a full academic article at a later date.

Arsenic

Arsenic was also a murder weapon, it accounted for 47% of known criminal poisonings in Britain. 42% in France and 57% in Belgium. Arsenic was easy to get hold of and used commonly in household tasks (notably getting rid of rats) so could be bought with ease. It doesn’t have a strong taste so could be slipped into food. It is believed that most people murdered by arsenic poisoning (rather than absorbing it though clothes, wallpapers etc) were fed it in small amounts over time, they slowly got sick and died, but the death was often not suspicious. Arsenic poisoning was usually then the result of an accident. Scattergood developed a method of pumping the stomach of someone with arsenic poisoning after he saved a child ate poison that was on the side.

With poisonings very few people had the skills to find the poisons. In courts it was usually only the prosecution that had tests done and judges usually believed doctors if the said poison was the cause. With this in mind Scattergood was often called upon to testify in court. The Marsh test for arsenic was developed in 1836 (collect and store yellowish arsine gas) and the Reinsch test in 1841 (shows heavy metals), both were used by Scattergood, but he also relied on taste and observation to verify his claims. He made efforts to improve his methods, but regardless in the northern courts his word was truth.

One of the most famous poisoning cases of the nineteenth century was Mary Ann Cotton, a woman who murdered (probably) 21 people, including husbands, her children and step children. She has been branded as “Britain’s first serial killer.” by criminologist Professor David Wilson two decades before Jack the Ripper. Her choice of poison was arsenic, favoured by murderers down the centuries for largely pragmatic reasons. First, it dissolves in a hot liquid, a cup of tea, for example, so is easy to administer. Second, it was readily available. Although by this stage, the authorities had started regulating the sale of arsenic, a high concentration could still be obtained in a substance known as ‘soft soap’, a household disinfectant. There was a third reason, too: as Mary Ann well knew, the symptoms of arsenic poisoning were vomiting, diarrhoea and dehydration. A busy and unsuspecting doctor was always more likely to diagnose this cluster of symptoms as gastroenteritis or cholera– especially in patients who were poor and undernourished – than to suspect murder.

According to death and burial certificates, all her victims had died of gastric ailments.It seems she also played the role of the grieving wife and mother to perfection, making it all the more difficult to be precise about the number of people she may have killed for thier life insurance.

Eventually she was caught, her sister in law (from her third husband) was suspicious when her brother and his children all died in quick succession. Three of Cottons’ children were exhumed from where they were buried in the garden of the local GP Dr Kilburn. Which is strange and suspicious in itself. Samples were taken from the bodies and Scattergood was able to detect arsenic in their remains. He had developed a new technique which required less tissue that the old tests. Cotton was tired and found guilty of murder and was hung for her crimes.

Bloodsplatters

The second forensic task I looked at what blood splatters, the key question for Scattergood at a crime seen was where did the blood come from? I was able to draw a series of examples from his notebooks where Scattergood developed his techniques

- On 26 Sept 1869 Scattergood asked to examine a pair of cords by inspector Murray of the Police. Asked to examine left knee and left cuff, both dry blood coloured. As reported in the book and newspaper Scattergood “examined this stain [knee] by the microscope and chemically and found it consisted of blood. The other mark was dark coloured soil. I am of the opinion that the blood is not that of bird or a fish. There are no means of positively distinguishing between human blood and that of any English quadruped. The appearances of it are consistent with it being human blood.” The jury charged the accused with murder of person or persons unknown. His name was kellet and a full account was in the Leeds mercury 29 September 1869.

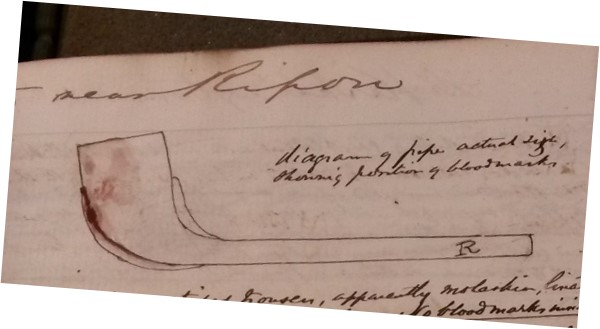

- Murder at Kirklington near Ripon. May 12 1874. Scattergood was sent 18 objects from the murder scene. He noticed In the case a pipe and some clothing had blood staining (other didn’t) Scattergood believed it to be a week old and having been washed A lady had been murdered, she was the widow of an ex-sergeant who lived with her four sons, she was a woman of “very dissipated habits” ie drinking, which exasperated her son. There was an incident were she was drunk, upset the eldest, her sons had a fight, she slept next door and had several accidents because of alcohol. Came back asked for tea, whilst tea was being made she died. Scattergood examined the body and ascertained that she died from a rupture of the vessels of the brain, this he felt was caused by a blow, not a fall.

- Scattergood received notice on 26 December 1876 that Jessie M Fitzakerly had been found dead 32 hours before. She had been intoxicated over Christmas and then visited friends and drunk more, walked home around 4 or 5 am but was unable to walk, nor was her husband. The wife fell on the doorstep when she entered the house she sat on a chair but sunk onto another. The friend left and there had been no quarrel, at 9 or 9.30 a neighbour called and the husband answered sleepily, about 11 the husband called for the neighbours as he could not find his wife. They found her at the bottom of the steps with her head on the bottom step and limbs pointing up the stairs, she was dead. When Scattergood saw the body it was “perfectly fresh”. There was blood at the bottom of the cellar steps and there was a bloody footprint 2 steps up caused by a woman’s boot, two steps higher another boot mark, there were 9 in all. The boots matched that of the friend who had taken them home. Some blood marks looked like they had come off a petticoat. The body when examined had a number of scuffs and bruises, but of note were 4 puncture marks on the right hand and abrasions and black bruises on the left and marks on the face including something that was not mud or blood. The back of the hair was soaked in blood” The internal organs were examined and found healthy (except the stomach which was thrown away without further examination). Scattergood and the other surgeons concluded that a violent fall backwards down the stairs would cause the injuries and probably caused her death but a violent weapon might have produced the same result. An open verdict was returned.

So there you go a super speedy introduction to the forensic work of Thomas Scattergood.

Leave a comment